Collective Impact: Shiny New Object or Real Solution?

Some people in the field are drinking the Collective Impact Kool-Aid like water in an oasis. Others are bristling at the thought of adding this big, hairy, complex additional thing to their already overfull plates. Who is right?

This post isn’t meant to define collective impact in any great detail, nor sway opinion in one direction or the other. If you want to know what it is, check out this primer by FSG, a mission-driven consulting firm that is at the forefront of the collective impact movement nationally. My purpose, in 300 words (or so), is to try to synthesize all of the information and insights I’ve gleaned from the myriad of meetings, readings and workshops on Collective Impact that I’ve taken in over the past several months (most recently, at today’s SINC: 2016 Conference). But don’t expect a firm answer to the title question. I can only express amazement at how polarizing Collective Impact has become in such a relatively short time on the block.

Funders and philanthropic pundits laud Collective Impact as The Way Things Should Be Done. They firmly believe that service providers should be working across sectors to address complex, entrenched problems. Services should be coordinated according to a common agenda. Organizations should communicate, partner and work towards a common result, informed by data and supported by a backbone organization that oversees fiscal management and data collection for the collaborative. All of these efforts should be aimed at reducing the negative statistics and/or increasing the positive ones, to achieve a population-level result.

Sounds great, right?

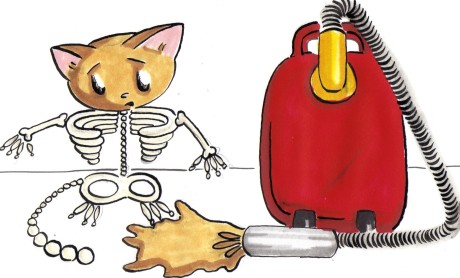

It does, until you ask the CEO who is in the process of completing an audit, preparing for a board meeting, and working frantically to meet a key proposal deadline while trying to fill a vacancy in the development department. Our poor, beleaguered CEOs are just too busy and distracted to add more meetings, more talking, more data collection, and more partnership strategies to the mix.

We can sympathize with them, right?

We can, unless (or until) it occurs to them that Collective Impact isn’t an additional thing to do; it’s a different way of approaching what they already do. And that’s the sticking point. Collective Impact requires systems-level change within all of the organizations that undertake it, and it therefore requires the organization’s leaders to change.

Collective Impact is messy and complicated. It takes time – years, decades – before you’ll ever achieve results. It requires relationships and partnerships that are “built at the speed of trust.” And it requires more funding than any one organization has, to achieve population-level results that no one organization can reach alone.

Sounds impossible, right?

And yet, it also minimizes isolation and allows service providers to better understand the larger context and environment that influences their work. When properly executed, Collective Impact increases efficiency and generates the kind of results that we all want.

Sounds like that’s what it’s really all about.

Right?